590

CHAPTER 20

We returned from Le Mans with the wind pretty well kicked out of our sails.

And we were just getting by with the company “sales.” I wasn’t around to get out there and dig out of the cars that worked well for us. The trip to France had, of course, run way past our cost projections and nearly emptied our coffers.

It was an awkward time . . .

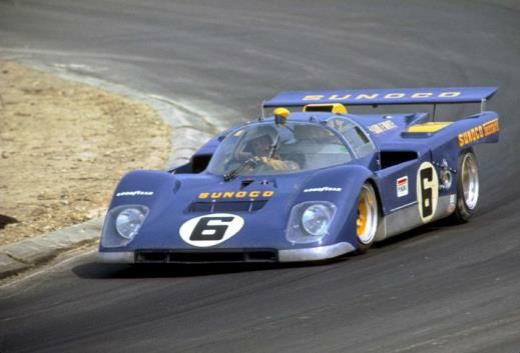

Less than a year ago the Ferrari 512 idea had been hatched, and Penske Racing had built the car into a world beater, which was so strikingly beautiful that it had captured the attention of not only diehard racing fans, but also the attention of other world’s well outside the auto racing fan base .

A great deal of the credit goes to the public relations efforts of both our company and Penske Racing. Certainly by 1971 Penske had already established itself as pretty much the reigning force in all forms of automobile racing.

Past that, our little organization, through the relentless efforts of the late Mo Campbell and our newsletter had gained a disproportionate level of recognition in the motorsports world.

The result of all of that was, when the Ferrari was presented for the 24 Hours of Daytona, an awful lot of people gave each other a knowing nudge and an air of:

“Watch that Penske/White Ferrari kick ass in this race! I mean the sucker had been built by the best team in America. That Ferrari’ll win it goin’ away!”

And those folks were right! Right up until midnight of the Daytona race when Mark was stupidly pushed up into the wall and essentially the entire left side of the car was wiped out!

Chapter 20

591

What unfolded then resulted in two teams pasting and taping the whole car back together. In the end, it not only returned to the fray, but it climbed from nowhere to finish third.

Then the car took on a whole new persona. The world was awash in images of the taped up gal pressing on. Duct tape sales in America jumped sharply up.

Then we went off to Sebring and almost every bizarre circumstance you could imagine befell the team. But again everyone pitched 110% effort into getting back into the race. I think Sebring 1971 may be best demonstrated by the incident that took place close to the end of the race.

It was an hour short of the end at 10:00 PM. Roger, in the cold dark, out at the wall, was signaling Mark, who was in sixth, that he was just a few seconds away from running down Vic Elford, encouraging him to push harder.

Mark was nowhere near Elford!

A close friend of Roger was with me watching from the pit wall. I looked at him skeptically and he smiled slightly, pointing at Roger:

“The guy never gives up . . .”

But, hey this whole damn effort had been put in motion to get to Le Mans wasn’t it?

And France ended with another star-crossed effort which we’ve all just gone through in the previous chapter . .

SO . . .

The final race for the Ferrari would be the Six hour event at Watkins Glen in just a few weeks, July 24. The following day there would be a Can-Am race. Many of the prototypes from the Saturday six hour would enter that Can Am big bore race. Our car had also signed on for the Sunday Can AM.

592

But wait, there’s a whole lot more to this season-ender. Penske Racing, after experiencing the double whammy of Daytona and Sebring, went on to a devastating series of disasters at the Indianapolis 500 just sixty days back when both Mark and David’s Indianapolis cars suffered a bizarre pair of mechanical failures, only to have their disabled cars smashed to smithereens by other cars in separate incidents!

What can you say about all the freakish events that befell the team in 1971.

(. . . I think I’ve used up my quota of “Star Crossed” . . .)

But all this re-hash is leading up to Penske Racing coming to Watkins Glen with a ten tenths effort. The car was spectacular in its presentation. Hell, Penske Racing could easily have taken the simple road, removed a few French sponsor decals, taken off the #11’s and slapped on #6. But they went through the whole car and the engines and arrived at the Glen like it was the inaugural race of the season.

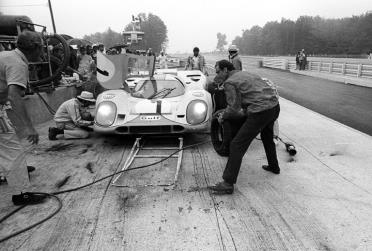

There was a strong presence of opposing Porsche 917’s, Ferrari 512’s and Alfa Romeo T33/3 prototypes. Among the Porsche 917’s were two from the Gulf/Wyer stable. Watkins Glen would be the final race for John Wyer with Porsche. Roger Penske Racing had been named to head up the dragon slayer 917 Can-AM effort.

There was also Mario Andretti in a Group 6 Ferrari factory 312PB and a one off 712 (!) Can Am Ferrari for Mario in the Can Am, Sunday.

And, finally Porsche had sent over a 917-1o for Joe Siffert to run in the Sunday Can-Am. It must have been an unholy handful, as Siffert, who was a rapid qualifier, could only land the beast in the eleventh starting spot.

(. . .Quietly, Mark, for the first time, informed Woody what was afoot for Penske Racing and next year’s 917 Porsche Cam Am effort. Mark told Woody to quietly have the eye on Siffert’s 917-K.)

593

“IT’S HORRIBLE . . .!!”

The Watkins Glen track was in the middle of a major overhaul and the paving job had been done in a hodge-podge fashion.

In spite of the track surface, Mark put the Ferrari on the pole with a qualifying lap of 1:o7.7, almost a second and a half quicker than anyone else. He qualified the 512, amazingly, in the sixth starting position for the Can Am race Sunday.

BUT, ENOUGH OF THE KIBITZING . . .

Right from the very start Mark took a decisive lead over the Porches and simply marched away from the rest of the field of cars. At the 50 lap mark he held a substantial lead of over nine seconds when he pitted for fuel.

The European teams that were there had been baffled and somewhat bemused by the Penske pit, with what appeared to be, a refueling rig that seemed to have the fuel all the way up in the air, for chrissake!! . . .

The rig had been utilized just once in 1969 for a Trans Am race at Michigan.

What the kibitzers didn’t know was that the tall rig had two containers, the outer one swathed the fuel in ICE! The rig had been outlawed almost everywhere, but it appeared Watkins Glen had no regulation against the set-up and they were OK with it.

Another example of the “Unfair Advantage” brought to you for your entertainment by Penske Racing.

All that aside, as Mark came in for his re-fueling, Jackie Ickx assumed the lead in the Ferrari factory 312PB, but within two laps Mark was back in the lead.

594

(. . . How can that be?? . . . Here’s how: That ice cold fuel coming from 24 feet in the air literally fell into the car! . . . Woody said Mark was in the pit fully fueled and out again in just over 2 SECONDS!! . . .)

Two laps later I watched Mark rip past the pits headed for the ninety degree right hander at the end of the straight and continued to watch as he drove straight off the track!

The stud that held the steering arm to the upright had simply snapped!

I witnessed the “off” and couldn’t believe my eyes. “How the hell could this be happening?” I thought. I couldn’t absorb it.

Always the very best preparation, the very finest drivers, everything done to the fucking nines, yet ending with no hits, no runs, no RBI’s.

And so it marked the end of the line for the Group 5 giants.

Many today feel it was the end of an era of the “real” endurance racers. Too fast they said, too dangerous, let’s tone it down.

(. . .Well looking at today’s goofy endurance racers, the computers that run them, the diabolical regulations such as the “balance of performance” and finally every team member, and that is every single one, including the kid who goes for the food is all trussed up in a fire suit, bobble head full face helmet, ad infinitum. . . .

. . . Sorry, sorry, I can’t just get past the joke that auto racing at this level has become . . .)

595

THE SUNDAY CAN-AM RACE. . .

The Ferrari was repaired after Mark unloaded some heavy verbal cannon-fire at the Ferrari factory guys who were there, telling them that they were providing stone-age inferior components for their racing cars!

With the Can-Am race underway, Mark was doubly disappointed in the track surface, being unable to handle the acceleration of the Can-Am cars, making for a tense time for all concerned.

Mark was running strongly even though the Ferrari was fully two liters in displacement under the Can Am cars. He was easily going to gain a top ten finish, when the engine failed with a holed piston . . .

THE END OF AN ERA . . .

Throughout the year I had gathered several like-minded people and mounted a petition to retain, or start, a venue for the Group 5 cars to continue to compete.

It struck me that it was ludicrous to relegate 25 Ferrari 512’s, and heaven knows how many Porsche 917’s, to storage or who knew what . . .

I attended the ACCUS meeting in New York with the petition.The idea met with sufficient interest to be sent on to the FIA in Paris where it was, of course, dismissed out of hand.

NO NEED TO . . .

Finally, there is no need to lament the evils that befell the effort with our Ferrari 512.

Rather, through these many years I have always been grateful. The entire experience remains an incredibly wonderful opportunity to have been a small part of the finest automobile racing team in America!

596

SO, WHAT HAPPENED WITH THAT “NEW” FERRARI YOU GOT, WHITEY . . .

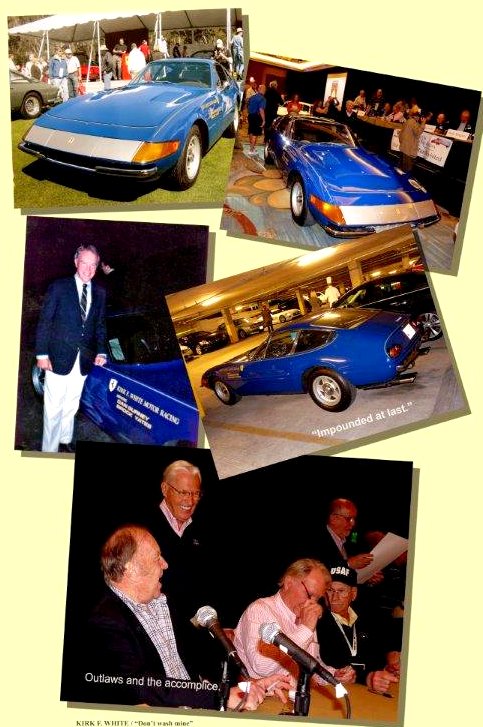

Well, that brand new 365GTB/4, serial #14271 came in the same sand beige metallic as my 275GTB/4, so it was shipped to Molin Body Shop where all manner of sacrilege was visited upon the poor Ferrari.

The car was refinished in Sunoco blue with the famed Larry Schoppett laying down some “modest” yellow pin striping.

Wait, there’s more: We radiused (word??) the leading corner edges of the hood. (If you didn’t radius them, the ninety degree corners would crack.) Then we “Frenched” the radio antenna.

Lastly, we immediately violated Federal Statutes and wiped away the goofy “U.S. Regulation” side reflectors. And, the smog pump belt just kind of fell off and we never could find a replacement . . .

The car came from the factory with the silver finish across the nose. We retained that accent.

Yeah, yeah, no Classiche for that gangster or any fancy show field invitations for that matter.

Sucker looked like a million bucks though!

So, what was your question? Oh, #14271 was pressed into service immediately as my driver for daily use.

I hadn’t had the car, but a short bit of time when I got a call one evening from my friend Brock Yates. The call came late in the evening. Brock had just finished drinks and a bit of dinner at Browns tavern in New York.

Brown’s was the favored after hours watering hole for many from the editorial side of Car & Driver Magazine. That evening, among others in attendance, were Steve Smith and Leon Mandel.

597

Brock was on a tear. A few from C & D wondered if he may have been at Brown’s all afternoon . . . He’d had an idea! He then spit out the following to his compatriots:

“What the world needs is a good old fashioned transcontinental race in the spirit of the early days of the automobile!”

A balls out, shoot the moon, screw the establishment rumble, coast-to-coast race from New York to Los Angeles!!”

Steve Smith was enthusiastically in! He thought it was the greatest idea since night baseball!

Mandel thought it was utterly stupid and not worthy of sticking around to hear any more about!!

Brock in reaching me enthusiastically outlined his Great American Dream!

Mmm, OK . . .” I said.

Brock went on to emphasize:

“I mean a balls out, shoot the moon, screw the establishment rumble, coast to coast from New York to LA . . .”

All I could say was: “. . . Neat idea!”

Then, oddly he added: . . . “And there ain’t nothin’ you can do about it!!”

“Uh, darn right!” was all I could think to say . . .

598

Had I been asked, I would have joined the group that felt Brock had been at Brown’s, way too long that day!

So, Brock was calling me to inquire if I might have a high speed vehicle that he and a noted co-driver could run the race with.

At that point it was well past eleven. I had to hit the road early for New York in the morning.

“Sure, you guys can have a cool car for the ride . . .”

I said that, figuring two things. One, the goofy idea will never happen, two, I wanted to get a bit of sleep before the vultures on Jerome Avenue in New York had at me.

Not so long after that call, there were several more, mostly running through how great it would be, but no solid ground yet. The idea didn’t gain any real legs until the end of August when Brock called with a real edge of excitement.

Robert Redford was going to do the run with Brock!

“If Redford signs on, do you think we might be able to drive your Ferrari?”

“Yeah, we should be able to provide you with a good Ferrari . . .” I said.

“I was thinking about your blue Daytona . . .” Brock said. “I mean Robert Redford is a major movie star!! He said.

“Okay, yes, you can have the Daytona as long as Redford’s the co-driver” I said, clearly thinking the chances were slim to none that that scenario would ever play out.

And, it didn’t. Redford’s movie team turned the idea down immediately.

Finally someone in this whole “Alice in Wonderland” skit had demonstrated some common sense!

599

Brock never took his foot out of the throttle. All manner of co-drivers were passed before me. Then Brock struck pay dirt.

Dan Gurney!

Hmm, things were amping up. I had firmly believed the crazy scheme would never transpire. Brock was set on running it in mid-November for some reason. It was then mid-October. I tried to put the whole thing in the back of my mind, but now Brock’s calls were almost daily.

First week of November, Dan called Brock and said that one or two of his sponsors were nervous about the run, and he wasn’t going to be able to do the drive.

I really felt badly for Brock. He’d really put his heart and soul into this wild scheme and had actually set the race idea fully in motion. It was to start at Midnight on November 15 of 1971 from the Red Ball Garage on 31st Street in Manhattan.

The night of November 13 the phone rang. I knew it was Yates . . .Don’t answer it, Kirk, no good will come of it . . . He was totally pumped.

Dan Gurney had carefully gone over the entire scheme, telephoned Brock and said he was taking the “red-eye” flight to New York.

Dan’s feeling was that this wild race idea was, as he put it: “The American thing to do . . .!!”

Well, that put a different face on it! “Okay, we’ll have the car there . . .”

I didn’t sleep too well that night. The next day Larry Schoppett lettered the Daytona and a few sponsors were quickly raised and slapped on the car. The day of the race I settled down quite a bit.

( . . .Hell, they’ll never make it out of New Jersey before they’re locked up. Worst that can happen is we’ll have to pick up the Ferrari at an impound yard somewhere in Jersey . . .)

I was so sure of that eventuality that I merely sent the car to New York. I wasn’t going to waste time with the start of that nutty race. There was a chance the whole “starting field might be arrested right there on the roof of the Red Ball Garage.”

600

I told Mo, get the damn car up there by 9:00 PM and don’t have anything to drink!

I went home and returned to the office the next day. Nothing. There was no news, no calls, simply dead air. The following morning we heard some vague report that they we doing well . . .

And, of course, Brock and Dan won the damn thing, crossing the country and punching in at The Portofino Inn on the Pacific in 35 hours and 54 minutes!!

Hell, I always knew they’d win the damn thing! Weren’t we all so clever to come up with that great cross country race idea that came to be not only repeated several times, but several movies were filmed! The ‘race’ Has continued in various iterations over a period approaching 50 years!

The “Cannonball Baker Sea to Shining Sea Memorial Trophy Dash” became an American cult icon.

Press coverage following the Cannonball race was off the charts. The first of two tremendously good accounts was written by the famed Sports Illustrated writer, Robert Jones.

In the “big” years of SI the magazine would often publish an in-depth multi -page article for the reader. Jones recounted the Cannonball race with a fantastic piece of writing.

For a great many years afterward it remained the most requested reprint in Sports Illustrated history!

But the story you’re about to read was written by the guy that was there, Brock Yates, for his book: “Cannonball! World’s Greatest Outlaw Race”

601

1971: The Race That Shook the World, By Brock Yates

From: “Cannonball! World’s Greatest Outlaw Road Race, 2002”

THE DRIVER’S MEETING WAS BRIEF. I outlined the Rule once again, noting that we would start from the Red Ball in one-minute intervals. The team arriving at the Portofino Inn in Redondo Beach in the briefest elapsed time – to be documented by the electronic time clocks at the Red Ball and at the Portofino’s registration desk – would be the winner. Beyond that, everybody was on his own.

The cars had been parked on the main floor of the Red Ball, lined up under the light of the bare ceiling bulbs. There was the Little Rock van with its spectacular red, white, and blue paint work; the red and white PRDA van, its flanks covered with sponsors’ decals and large type proclaiming: “THE POLISH RACING DRIVERS OF AMERICA GO COAST-TO-COAST NONSTOP!” By contrast, Moon Trash II had been painted, bumper to bumper, in a murky coat of flat black. Crouching beside it was our Ferrari Daytona, its mirror-polished, Sunoco blue paint glinting in the raw light, its elegant finish highlighted by a masterful network of yellow pinstriping and its fenders amply covered with decals from sponsors that Kirk White’s staff had attracted to help defray expenses. Gurney’s and my names were displayed in neat lettering under the windows. It had been the first time I’d seen the car up close. “It’s been cunningly disguised as a racing car!!” I gasped.

Wind was kicking up litter on 31st Street as the midnight starting time approached. While the first four cars departed, Gurney and I went off to gather up some provisions at an all-night delicatessen.

We rolled the Ferrari out of the Red Ball and onto the dark street. As a cluster of friends stood by, Gurney and I fitted our gear around the seats and wound ourselves into the elaborate seat belts and shoulder harnesses. We were set. Already the PRDA, the Cadillac, and MG, and the Little Rock van were on the road. Moon Trash II would leave half an hour after us, while Broderick’s motor home and the Bruerton brothers would depart later in the day.

Dan would drive the first leg. He cranked the engine over, and a potent, whirring rumble rose out of the Ferrari’s long hood. He flipped on the headlights and the black leather cockpit glowed with the soft green luster of the large instrument panel. A friend stamped out tickets on the Red Ball time clock – our official record of departure – and amid a tiny chorus of windswept cheers, we accelerated away, roaring down 31st Street toward the Lincoln Tunnel and California. We went about 200 feet. The stoplight at the corner of 31st and Lexington winked red as we approached, and we sat there through its full cycle. Every cross-town light then conspired to stop us, and we were immobilized at seven intersections before reaching the tunnel.

602

Our route was to be different from the others’. While most planned to cut directly westward to the Pennsylvania Turnpike, I’d decided that a more northern route across Interstate 80, with a subsequent cut south to Columbus, Ohio, was fastest. It was a trifle longer, but I-80 had less traffic and fewer patrols than the Turnpike and appeared to permit higher cruising speeds. It had to be reached via a series of two-lane roads in the daytime. However, in the deep of night and with Dan driving with relish, we traversed the slow section with an average speed that approached 60 miles per hour.

Gurney began to hit his stride as we reached the broad expanses of Interstate 80, He was cruising the Ferrari at 95 miles per hour-a virtual canter. At that speed, it was so positively in contact with the road that Gurney complained it was boring to drive. To understand the excellence of a machine like the Ferrari one had to have driven a thoroughbred sports car. There is no other way.

Lights appeared behind us. Thinking it might be the highway patrol, we backed off slightly and let the car overtake us. It was a Camaro with a man in his early 20s at the wheel. He was cruising at about 100 miles per hour. Gurney watched him sail past, then accelerated to keep pace. I knew he wouldn’t let the Camaro stay ahead. He opened the throttle plates on the Ferrari’s 12 carburetor throats, and the big car clawed ahead, gobbling up the distance between it and the Camaro. We rocketed past. The engine noise increased slightly, but hardly to objectionable levels. The Camaro’s headlights dwindled in the distance.

“That’s 150, just as steady as you please,” said Gurney. Then he laughed.

Dan eased back to an indicated 120 miles per hours and we cruised down the deserted road, cutting over the humpbacked Allegheny Mountains of central Pennsylvania without effort. Gurney was driving with one hand and drinking coffee with the other when he sighted a dim pair of taillights far ahead. Again, it could be the police, so he slowed to about 100 and approached cautiously. I had 20/20 vision. I saw well at night, yet I was still trying to get some rough identification of the vehicle ahead when Gurney announced, “It’s OK, it’s only a Volkswagen,” and got back on the throttle. Sure enough, it was a Volkswagen lumping along there in the dark, and I silently pondered the power of Gurney’s eyesight. It is said that most great drivers possess uncanny eyes, but I had never taken that seriously. Now I was a believer.

I napped sporadically while Dan sailed onward, running for an hour in excess of 100 miles per hour and increasing our trip average to 81 miles per hour. That was exceptional time, but neither of us expected it to hold up across the country. Three hundred miles from Manhattan when we stopped for gas, I had leaped out and stuffed

603

the pump nozzle into the tank before the sleepy attendant had gotten out of his chair. Dan, in the meantime, had lifted the hood and was making a routine check of the oil. This pit stop procedure would be repeated for most of the trip, with me concluding the stop by stuffing a wad of dollar bills (brought specifically for that purpose) into the startled attendant’s hand, leaping into the Ferrari, and spurting back onto the highway. In this manner we were able to keep most of our stops under five minutes.

Again, Gurney’s miraculous eyes identified another pair of taillights. This time it was a Pennsylvania Highway Patrol Plymouth, and we slowed accordingly, falling obediently into his wake a 65 miles per hour. It felt like we were walking. We reached Columbus in six and a half hours. We were one hour ahead of the time I had run with Moon Trash II and were averaging 81 miles per hour. We presumed we were far ahead of the rest of the entrants.

Dan had been at the wheel nearly 12 hours when we reached St. Louis. He claimed he felt fine, and I believed him. After years of being around automobiles, one can sense a change in the reactions and movements of a driver – his very cadence with the car alters – when he becomes fatigued. Gurney was in excellent shape. As the traffic got slightly heavier west of St. Louis, we backed off our speed to about 85 miles per hour keeping a steady eye open for the law. We passed three pimply youths in a GTO, and they tried to race us. Gurney, racer to the end, responded. The Ferrari shot ahead and, witnessing that awesome burst of acceleration, the boys gave up.

I took the wheel for the first time in mid-Missouri. Dan had driven 14 hours and 35 minutes. A long time to be sure, but with the near-mystical ease with which a Ferrari gobbles distance, the time becomes less amazing. “This thing is a whole new dimension in driving,” I said as I accelerated onto the deserted Interstate.

The sun dropped behind a thick bank of clouds in the west, luring us into our first full night on the road. I drove for eight hours before Dan took over. We were maintaining our average speed at 83.5 miles per hour. As we reached the New Mexico border, a nasty thunderstorm lit the sky with orange fireballs and sent sheets of rain pelting against the windshield. It turned to sleet, and thickets of fog lurked in the dips of the highway. But I slept. With a man like Dan Gurney at the wheel, I think I could have rested if we’d been traversing the South Col of Mt. Everest.

We reached Albuquerque in the 24th hour of our trip, convinced that not one of our competitors was within three states of us. As we stopped at Gallup, New Mexico we spotted several approaching cars with their grillwork smudged with snow. We had just crested the Continental Divide and were heading for the high country of eastern Arizona. If we were to encounter ice, it would be in this dark and desolate stretch. I called the Highway Patrol from a gas station, while the attendant leisurely filled the tank and Gurney sipped a can of hot soup from a vending machine.

604

We were getting cocky, and the urgency of our earlier stops had given way to a kind of relaxed elegance reserved for big winners. The phone operator at the Highway Patrol was vague: some snow squalls, some fog, perhaps a little ice, but nothing alarming With the temperature sitting somewhere in the low 30s, I took the wheel and headed for the mountains knowing that conditions were perfect for hellish weather.

I might as well have talked to the Highway Patrol in Honolulu. The lights of Gallup still winded in the valley below when the highway became sheathed in a thick layer of slush, punctuated by long stretches of hard ice. First came the fog, then fat lumps of wet snow that flung themselves into our headlights, cutting visibility to zero. The Ferrari was slewing all over the road. It was nearly uncontrollable, and we couldn’t understand why our wonderful machine had become so inept in the face of this nasty but hardly unusual squall. Dan figured it out. He recalled that the Kirk White crew had increased the tire pressure to 40 pounds for added safety and efficiency in the high-speed dry stretches. Apparently they hadn’t anticipated snow. The tires of course! As we were debating whether or not to stop and cut the pressure to perhaps 26 pounds - which would mean a double penalty with more time lost when we hit the desert to re-inflate - a quartet of headlights blazed in my mirrors. A car was overtaking us at a high sped, seemingly navigating the ice without difficulty. It disappeared in a patch of fog, then surged alongside and swept past. It was a cream-colored Cadillac. Gurney and I paid it little attention, still engrossing in strategy talk about what to do with our slipping tires.

“Jesus Christ, wait a minute!” I yelled as Dan was in midsentence. “That Cadillac. That thing had New York plates! That couldn’t be those three guys from Boston!” Or could it? Stunned, even horrified that any other competitor could be that close, we pressed on, trying to narrow the distance between us and the fleeting Sedan DeVille. “If those guys are with us, where are the PRDA and some of the others” I said bitterly.

The lights of the agricultural inspection station on the New Mexico-Arizona border loomed out of the fog and snow. A car was stopped under the canopy. Its trunk was up. A smiling man with a heavy shock of black hair was standing beside the machine - a cream-colored Cadillac with New York plates – while a uniformed official probed through the luggage.

“Oh, s**t, that’s Larry Opert,” I moaned. “Those are the guys, and they’re blowing our doors off!” They squirted away into the night as we stopped for our inspection. Realizing there was precious little room for any dangerous quantities of wormy peaches or infected chickens to be stowed on board the Ferrari, the officer let us pass after a few routine questions. Our cockiness of a few miles back had given way to shocked despair. Our only comfort lay in the knowledge that the Caddy had started about 20 minutes earlier and was therefore still behind us on elapsed time. But what about the others?

605

Surely somebody was in front of the Caddy. “Us cruising across half the damn country figuring we were hundreds of miles ahead, what a bad joke that was,” I mumbled as I rushed through the black, fog-shrouded night. Fortunately the roads were improving, and while they remained wet, the ice was disappearing. The fog lifted for a minute, and we saw their taillights perhaps a mile in front. As the road and visibility cleared, we began to gnaw at their advantage, although the Cadillac seemed to be running in the neighborhood of 100 miles per hour on the straight stretches. Mile after mile we traveled, losing them for long periods in the gloom, then catching tantalizing glints of red up ahead. We had them in sight by the time the outskirts of Winslow, Arizona, were breached. They pulled into a gas station. As they leaped out under the bright lit canopy, I gave them a blast of the Ferrari’s air horns.

We were fully awake now, vibrating with the idea of the newfound competition. We had not sought it out; in fact we would have been perfectly contented to putter on toward California at a leisurely pace. But now that the Cadillac was surely thundering down the road behind us, its gas tank topped off and set to run for hours, we readied ourselves to play our trump cards. That meant Dan would take over at Flagstaff, in preparation for a run down our secret shortcut-a pair of moves that night put us back into lead. My earlier run with Moon Trash II had revealed that by taking Arizona Route 89 south to Prescott, then cutting toward the desert and Interstate 10, we could trim at least half an hour off the trip. To our knowledge, everyone else would take the conventional old Route 66-Interstate 40 network that was slightly shorter but more congested. Admittedly, our route was more dangerous. It involved negotiating the endless switchbacks on the 15-mile stretch of Route 89 through the Prescott National Forest and the murderous plunge down a mountainside south of Yarnell, where the road featured minimal guard rails and 1,000-foot drop-offs.

Our stop for gas in Flagstaff was slow simply because the pumps of that particular station moved fuel into our tank at a rather lazy rate. By the time we got under way again, with Dan driving, the Cadillac had caught up. We immediately passed it after returning to the Interstate. Opert and Co. were running the big crock at its maximum, perhaps 115 miles per hour, and it was easy to see how they had not lost any time with their stop. Their tank was smaller, and therefore more quickly filled, and their top speed at night was only a few miles per hour less than ours. They were back in contention.

Gurney was opening gobs of distance on the Caddy as we rushed down the winding pine-bordered four-lane. It was a lovely stretch of road made even more beautiful by the thick layer of snow that had fallen on the trees earlier in the night. But the highway surface seemed clear, and Dan was running 125 miles per hour when we sailed onto the bridge that was part of a long downhill bend to the left. It was covered with a glaze of ice. Suddenly Gurney was jabbering and his hands began a series of blinding twists of the wheel “This is glare ice! Glare ice! This is BLEEDING GLARE ICE!” he repeated with increasing volume as he slashed at the steering wheel.

606

I had been in the middle of a statement about something (I cannot recall the exact subject) and I remember that I kept on blathering throughout the trip across the bridge, as if my brain had decided that, if I did not acknowledge Gurney’s alarm, perhaps the ice would go away. Thanks to the talents of Gurney, we traversed the bridge with merely a slight twitch of the Ferrari’s tail. Because he so skillfully maintained control of the car, only he will ever know how far beyond the ragged edges we had traveled.

“That’s enough of the s**t, said Gurney firmly as he slowed down. “Race or no race, we aren’t going to wipe ourselves out on ice like that. Man, that was scary, and I don’t mind telling you I didn’t like it one bit!”

“God, I wonder about the Cadillac. I sure hope those guys get across the stretch all right,” I said. We cruised onward, our speed reduced to a modest 70 miles per hour. I was relieved to see the Caddy’s lights pop up behind us. They had slowed, indicating they, too, had encountered a few thrills on the bridge.

“That would have been a helluva crash,” I mused. “And just think, not a soul within miles to see it. Most of your crashes take place in front of thousands of people. What a switch this would have been.”

A tactical problem was arising. With the Cadillac cruising behind us, it was possible that they would trail after us on our shortcut. The turn to Route 89 was only a few miles ahead at Ash Fork, and we somehow had to get the Caddy out of sight before then. Outrunning them was impossible, considering the treacherous roads. Our only choice was to let them pass then drop back and make our turn as they sped ahead.

“Hey, slow down and pull over on the shoulder,” I told Dan. “Maybe they’ll just drive past and we’ll let ‘em get out of sight before restarting.”

Gurney stopped the Ferrari on the roadside The Cadillac pulled over too, drawing alongside as it came to a halt. We switched off our engine and sat there in the still, clear mountain night. The three men in the Cadillac looked haggard and hollow-eyed, obviously fatigued from the run.

“How’d you guys like that icy bridge?” Dan asked through his open window.

“Bad s**t. We thought we’d had it” said a voice from inside the Caddy.

We chattered for a few minutes about the various adventures we had encountered. They reported that so far they’d been stopped by the police four times. Gurney started the Ferrari’s engine, preparing to leave. The Cadillac hesitated, as if to follow us onto the road in the original order. “Go ahead. You guys go first,” said Dan casually. “After all, we’ve got a 20-minute lead on you.” Taking the bait, the Cadillac scurried away and rushed down the road. We followed at a discreet distance, letting them get a half-mile ahead. By the time we reached the Route 89 turnoff, they were out of sight.

607

Thanks to the lower altitude, the road to Prescott was bare and clear of ice or any evidence of precipitation. It was a wide level stretch of two-lane, virtually deserted, and Gurney ran the entire 51 miles with the speedometer needle glued to 130 miles per hour. Whisking through Prescott and not seeing a soul on its streets, we plunged into the National Forest. Mile after mile of tight mountainside switchbacks whispered underneath us. Gurney’s masterful times and discipline became apparent with each passing yard.

The nasty cut beyond Yarnell was traveled with similar ease, and suddenly we were on the desert floor. Flat, open road lay between us and Los Angeles. Dawn lit the way and Gurney upped the pace to 140 miles per hour across the desolation. Not even a stray jackrabbit or a tumbleweed was moving in the morning stillness; only the rounded, bullet-shaped Ferrari shrieking southward toward Interstate 10 and possible victory.

HE CAUGHT US ON A BACK STREET in Quartzite, Arizona. I had spotted his car, a mud-brown Dodge Highway Patrol sedan, parked in front of a run-down café at the roadside. The car had been empty, indicating that he’d been having his morning coffee when we’d ripped past, doubtlessly rattling the windows in the little place. I’d told Gurney about the car, then kept my eyes focused on the café, watching for movement. I saw headlights flick on. “He’s coming. He’s chasing us.”

“He’ll never catch us,” Dan said firmly.

“He’s gaining. He must be running 140 miles an hour!” I reported.

We sat there, speeding along in limbo, trying to figure out what to do. There was no sense trying to elude him on the side road. There were no side roads; outrunning him was out of the question. A short distance ahead was the Arizona-California border on the Colorado River. He could easily radio ahead and stop us at the agricultural inspection station. We drove onward, as if in a trance, letting him close the gap. “We’ll turn off in Guartzite and get some gas. Maybe he’ll miss us,” said Gurney. He sailed onto an off-ramp and scuttled down a back street. Sighting an empty self-service gas station, he raked the Ferrari to a stop. Perhaps our pursuer in the mud-brown Dodge hadn’t seen us get off the Interstate.

He had. In fact we had barely shut off the Ferrari’s engine when the boxy form of the Dodge, its twin gumball roof lights flashing crazily, skidded to a halt in the gravel beside us.. A tall patrolman in a starched khaki uniform leaped out. He was wearing a crash helmet. His glands still pulsing from the pursuit, his feathers ruffled in a kind of cock-rooster triumph, he marched over to Gurney and curtly demanded his license and

608

registration. Little more was said as he strode back to his car and removed a pad and pencil. We stood there, the silence broken only by the furry, electronic jabbering from his radio and the hushed background rumble of an occasional passing truck. He obviously recognized Gurney and for a few minutes hope rose in us that he might issue a stern warning and send up on our way. But he kept on writing. A summons was being issued and a hardness crept across Dan’s face.

Ripping the ticket off the pad and handing it to Gurney, the highway patrolman, as if to signal the end of official business, turned to regard the Ferrari for a moment, then asked rather affably, “Just how fast will that thing go?”

“C’mon out on the highway, and we’ll let you find out,” Gurney snapped.

Fortunately, the officer chose to take Dan’s crack as an attempt at humor and let us go. Although he had spared up the agony of being dragged off to a justice of the peace, which would have consumed perhaps an hour, the incident had used up at least 10 minutes. “That does it we’ve probably lost for sure,” I said dejectedly as we pulled back on the Interstate.

An evil smile spread across Gurney’s face. “He was wondering how fast this thing will go. Let’s find out.” The Ferrari began to gain speed, whisking easily at 150 miles per hour. The car felt smooth and steady. There was not much wind noise, considering the velocity. “There’s 170!” said Gurney. The needle pushed its way around the big dial, then stabilized at 172 miles per hour. Gurney laughed. “This son of a b**ch really runs,” he said in amazement. “And it’s rock steady.” He took his left hand off the wheel, and we powered along toward Los Angeles, the Ferrari rushing through the desert morning at 172 miles per hour.

“You think we ought to turn back and answer the cop’s question?” I asked. But our amusement from the 172-miles-per-hour run was only temporary. As we slipped back to a more normal cruising speed, we both decided that the delay from the arrest has ended our chances of winning the Cannonball. “Those other guys have to be miles ahead by now,” I grumbled. We stopped for gasoline in Indio, California, where our general discouragement led to more torpor and lost time. Once on the road again with the end in sight, we managed to perk up, drawing on our final reservoirs of energy “Listen, at least we ought to try to make the trip in under 36 hours,” said Gurney “If we can do that, we can’t shame ourselves too badly.”

We were back in it again, running hard. To reach our goal, we had a little over two hours to run about 130 miles – practically all of it over heavily patrolled Los Angeles freeways. “You watch out the back for the Highway Patrol, and I’ll run as fast as I can” said Dan. I turned in my seat, scanning the off-ramps and the passing traffic for the familiar black-and-white California Highway Patrol cruisers. Gurney drove through the building traffic

609

with incredible smoothness, seldom braking and never making severe lane changes. We turned off at the Western Avenue exit and bustled through three miles of heavy urban congestion, heading for Redondo Beach and the Portofino Inn. The masts and spars of the yachts moored in the Redondo Beach marina appeared, and Dan accelerated the Ferrari the last few yards into the Inn’s parking lot. I was out of the car before it stopped moving and sprinting into the lobby, where a pair of mildly shocked bellhops looked up to see an unshaven, grubby form for rush up to the desk. The clerk punched our ticket.

Our elapsed time was 35 hours and 54 minutes. What’s more, no one else had arrived. We were the first car to finish. – BROCK YATES.

And now you know the rest of the story!

Well, almost. The two waited for the rest of the finishers and they all celebrated happily. Most all of the highway adventures were wildly exaggerated and everyone was thrilled to have mustered the chutzpah to run the damn race!

A day or two later Brock said he was heading back in the Ferrari, taking a lazy zigzag route he’d always wanted to drive.

Life went on and I very nearly forgot about the Ferrari. Then I got up one morning, literally weeks later and as I was going out the door to whatever car I’d driven home the night before, there sat the Ferrari Daytona in the driveway.

I believe I actually groaned. I walked around the car expecting to witness a trashed to death car. It looked terrific. Clean as a whistle inside and out. The keys were in the ignition. As I got in the car, I noticed the rear tires were totally bald. I remember thinking: “. . . alright this baby is worn to a frazzle, you’ll have to come up with a bunch of pretty clever words to get this thing sold . . .”

Not so. The car ran just a tad better than when I’d given it to them; there were no rattles, no dings, no dents, no scratches. The entire drivetrain was superb, clutch, gearbox, all of it. Astonishing!

I put four new Michelin XWX’s on and drove the Ferrari forever. . .

COMING NEXT:

Chapter 21, Thursday, December 15

“Going into 1972 . . .”

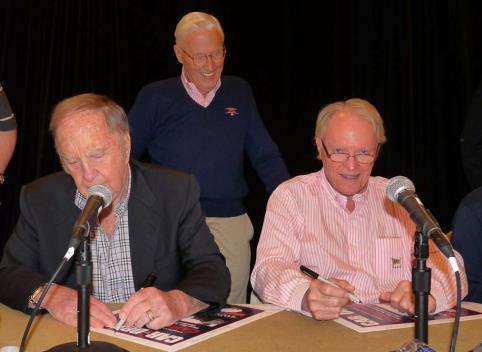

"Cannonball Reunion, Amelia Island, 2011"

Brock Yates, Kirk White, Dan Gurney

This Chapter is dedicated to my friend, the incomparable . . . BROCK YATES